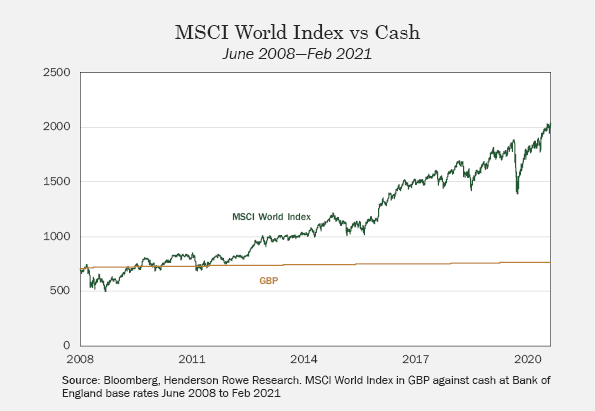

One summer, several years ago, a very close friend of mine had just had her first child. Her newborn was the beneficiary of a Government scheme to ensure that children had some kind of nest egg for education or living alone when reaching maturity: a Child Trust Fund. All babies received a £250 government gift with a further £250 when the child turned seven. My friend discussed with me where she was going to place the money and I suggested an equity tracker fund. She then inquired whether this could lose money and I had to admit that it was a possibility. My friend quickly decided she would therefore keep the money in cash. I doubted at the time but resisted the temptation to criticize her decision. If fact, (and hindsight is a wonderous thing) had the funds been placed in a world tracker fund twelve years ago, topped up seven years later, this pot would now be worth more than £11001. But, in order to achieve this, she would have had to endure a painful short-term loss in the 2008/09 market downturn which saw shares shed as much as 50% of their value: this requires either a sense of recklessness, a strong stomach or losing your login credentials. It was later the same year that I met up with a (non-financial industry) schoolfriend after several years who politely let me whitter on about my fabulous new job before mildly enquiring after 20 minutes, “What’s ‘FX’? ” (the industry shorthand for foreign exchange).

Jargon and risk aversion: these were some findings of what appears to have been an extensive survey by Fidelity International2 about the investing habits of women, and why they make up so small a proportion of investment management clientele. We know that women are good savers: 8% more women than men contributed to an ISA in 2018, however they contributed to cash ISAs with 21% fewer women contributing to a stocks and shares ISAs than male counterparts3. As at March 2018, astonishingly, 61% of women in the UK were making no contributions to any private pension scheme4. We know that women live a lot longer (7 in 10 people over 90 are female5) and tend to earn less6 over the course of their working life. Living longer and earning less, women have far more need to put money aside and earn solid investment returns, but the industry is somehow failing them, and with 53% of UK millionaires predicted to be women in 20257, it pays to get this right.

Although it seems that women invest less than men, those who do so, seem to do it well. Analysis by Hargreaves Lansdown8 found its female clients’ portfolios outperformed male client portfolios by 0.81% on average each year. They were more likely to hold well-diversified portfolios, rather than to concentrate risk in one area; they were also less likely to choose ultra high-risk investments and tended to trade less frequently, adopting a buy and hold investment strategy and not racking up the trading costs of their male counterparts.

Risk, or more precisely risk-aversion, does seem to be a reoccurring theme. Research by Sundén and Surette (1998)9 found that gender is significantly related to asset allocation and Hinz, McCarthy and Turner (1996)10 find that women invest more conservatively. Low risk investments, such as cash or government bonds, offer relatively lower returns because of the security of the investment and are deemed more suitable for risk adverse or ‘conservative’ investors. But there is a long-term risk/return trade off. The more risk you are willing to take, the more potential there is for return in the long-run, however there is also more potential for loss in the short-term and it is these short-term losses that make investors queasy: who is thinking about 10 years’ time when watching the markets collapse 8% one day in February because of COVID?

Doug Sundheim11 considers that perhaps men and women view risk through different lenses citing that men see risk in the framework of whether it helps them achieve a strategic objective whereas women see risk as the impact that it will have on the people around them. This idea ties into the finding of a Wealthiher survey which identified that 59% of women regard their wealth as security for the family and children12. Sundheim concludes the most successful risk taking, leading to the best (business) outcomes, are when men and women work together collaboratively. Rather than taking note of this, over the past decade, the investment industry’s response to too few female clients has been a rampage of recruiting, retaining and reattracting experienced female talent to the business. The implication being that more women will become clients if only they could speak to another women. But this may be misplaced. A study by King’s Business School found that both male and female advisors put female investors in a lower risk bracket but that female advisors did this to a greater extent. We can conclude from this that female investors may be better off, literally, with a male advisor. Furthermore, if an investor, male or female, is placed in a lower risk bracket than their tolerance, the returns might seem miserly against the fees, deterring them from future investment. The unanswered question here, which the industry should address, is: are these findings a reflection of risk tolerance, actual prejudice or do women simply respond in a more conservative fashion when questioned about risk? It is well studied that women rarely advocate for themselves and generally “don’t ask”13: there is no reason to think this same practice doesn’t apply to investment services.

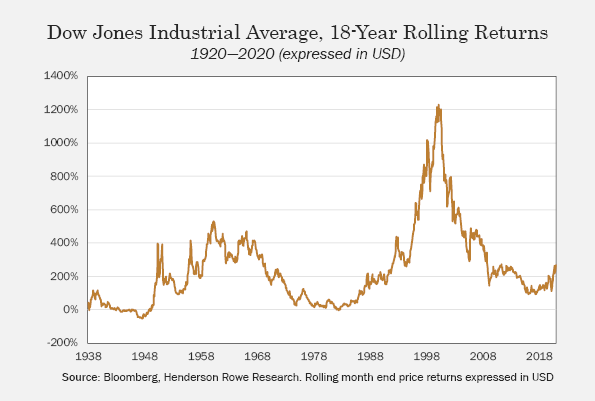

Perhaps I did my friend a disservice all those years ago. Perhaps I should have explained that in the last 100 years there has seldom been an 18 year period (the time to the maturity of the Child Trust Fund) where equities have made losses. Unfortunately, we rarely hear about market gains in the news which might give a disproportionate sense of risk. Through all the roller coaster rides of my lifetime: the ’87 crash, Russian debt crisis, dotcom bust, GFC and now coronavirus, the index level has always reverted to mean. This isn’t to say that they always will of course, and some might prefer the comfort of staying in cash “just in case” but it is equally important to understand that “growth and comfort do not co-exist”. IBMs CEO, Ginni Rometty was referring to personal growth, but the same principal applies to investing.

In my opinion, treating men and women as homogeneous groups that fit into uniform behaviours is the biggest challenge the industry faces. Although studies show men and women have different traits, we have more in common than that which divides us. A good wealth management service is personalised; it understands the needs of its client, talks in a way that the client understands without being condescending, creates a safe space where the client feels they can ask any question and helps the client understand their true risk profile so they can maximise their returns within those parameters. This is simply a good service and should be nothing to do with the gender of either the advisor or the client. If male advisors are not providing this for female clientele then perhaps we should ask the men rather than the women to do the adjusting.

1Assumes investment in MSCI World Index 30.06.2008 and 30.06.2015. GBP returns.

2The Financial Power of Women, Fidelity International

3Individual Savings Account (ISA) Statistics, HM Revenue & Customs, June 2020

4UK Pension & Wealth Data (5 December 2019 release), Office for National Statistics

5UK Population Pyramid Interactive (mid-2018 release), Office for National Statistics

6Global Gender Gap Report 2020, World Economic Forum

7FT.com, 23 May 2019 “Wealth managers adapt to appeal to female clients”

8Nicholas Hyett, Hargreaves Lansdown “Do women make better investors?” (29 January 2018)

9“Gender Differences in the Allocation of Assets in Retirement Savings Plans”, Sundén and Surette

10“Are Women Conservative Investors? Gender Differences in Participant-Directed Pension Investments”, Hinz. McCarthy, Turner

11“Do Women Take as Many Risks as Men?”, Doug Sundheim, Harvard Business Review, 27 Feb 2013

12FT.com, 23 May 2019 “Wealth managers adapt to appeal to female clients”

13“Women are still not asking for pay rises. Here’s why”, World Economic Forum, 12 April 2018

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Henderson Rowe is a registered trading name of Henderson Rowe Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under Firm Reference Number 401809.

The information contained in this article is the opinion of Henderson Rowe and does not represent investment advice. The value of investment may go up and down and investors may not get back what they invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.