Back in 2013, the Harvard Business Review published an excellent article by Tomas Chamorro- Premuzic, a professor of business psychology at University College London. The article, Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders?, made many interesting points. One of the key takeaways was this: The very attributes that lead to a manager being chosen are the same ones that make him a bad manager. This article was about managers of businesses, but the insight rings just as true for portfolio managers.

One of the most shocking revelations for business school students in a core management/leadership class is that lessons from the biographies of the most iconic business leaders are almost negatively correlated with the identified traits of effective leaders documented by academics in large-scale studies. Research shows that practices which lead to sustained and repeatable firm successes are humility, listening, adaptability, vulnerability and— importantly—openness.

It’s possible the ivory tower academics have no idea what they’re talking about. After all, biographies of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk might suggest that great leaders have all the answers, never doubt themselves, manically push forward despite conflicting evidence, are able to will an outcome into existence through positive thinking and—this one’s key—are comfortable making big bets. One imagines that if failed CEOs were also asked to write books you would find almost identical characteristics.

What is often true of people who are chosen for a senior leadership position is that they have previously made unreasonably large bets, driven by overconfidence. And those bets happened to pan out. The overconfidence allows them to take credit with enormous conviction for an outcome largely driven by luck. The very basis for their promotion to leadership—taking big risk due to hubris, taking credit for luck—is the same reason they fail as senior executives after ascending to that position.

The same is true of investment managers and the process by which they’re selected. Fund managers perched on top of last year’s performance rankings typically run heavily concentrated portfolios loaded with big industry and single-stock bets. Bottom performing managers, one finds, hold different stocks, but are identical in their risk-taking. If you interviewed both sets of managers, they would offer compelling and well-researched investment theses. Both would have enormous conviction and would eat their own cooking. You would have trouble deciding, ex ante, who would turn out to be right. All you would know is that given their conviction and their concentration, they must either become a positive outlier—and a top-performing manager—or a negative outlier and destroyer of client wealth.

Despite the strong similarities between top-performing and bottom-performing managers, human behavioral biases repeatedly drive investors to choose managers with the best recent performance. Much of the allure apparently stems from the myths such managers cultivate about themselves: stories of unwavering conviction in the face of significant volatility, of steadfast certainty in the trade. That’s a story that few investors can resist. But the very characteristics that lead to the selection of such managers—taking big risk due to hubris, taking credit for luck—ultimately doom these managers to be irresponsible stewards of client wealth.

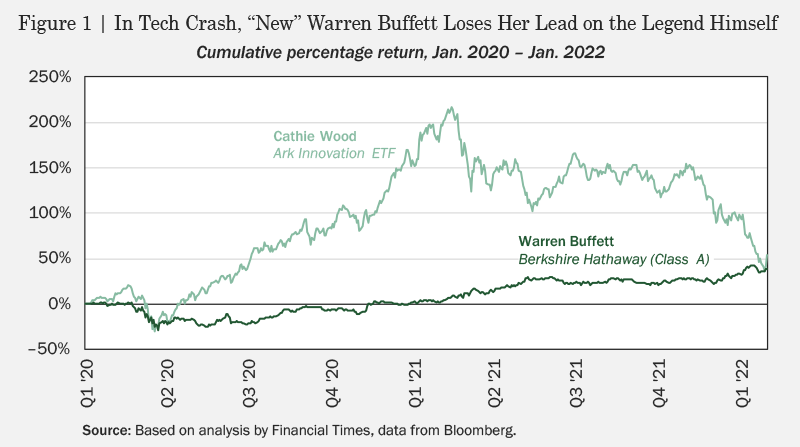

Cathie Wood, manager of the Ark Innovation ETF (ARKK), is perhaps the most recent in a long line of investors anointed as the ‘New Warren Buffett’ for her performance since the pandemic began. Most investors would love to have allocated to her fund at the beginning of 2020 (and most managers would love the 30-fold increase in assets she enjoyed following that great performance). But the characteristics that made ARKK successful in 2020 played out quite differently in the following year, when the fund declined 50% from its peak, wiping out US$25 billion of clients’ assets in the process. Many of us will recall an older incarnation of the ‘New Warren Buffett’, John Paulson, proclaimed the investor of the century for betting against subprime mortgages just before the global financial crisis. He subsequently raised $32 billion in assets, then lost 70% of his investors’ wealth.

Wood and Paulson likely have many good qualities as portfolio managers—they are undoubtedly very skilled as entrepreneurs—and the point of these examples is not really to critique them as investors. Instead, we consider these cases to illustrate a shortcoming in the way individuals (and even sophisticated institutions) choose investment managers. Every portfolio manager has some kind of process, but what Wood and Paulson and most of the top-performing managers in any given year have in common—and the reason that they attract so much attention and such large inflows from new investors—is that their process was connected to a theme, and that turned out to be the theme of the year.