Market Overview

Equity investors did not need to head for the snowy heights over the year end break. The heights came heading straight at them in a truly monster Santa Rally. This capped a year in which the S&P 500 added over 30% from the depths of a capitulation sell-off on Christmas Eve 2018.

Much of the credit for 2019’s performance belongs to the Fed, generously pumping $100 billion into the system every month, but kudos too to quoted US companies, whose $600bn of share buybacks has been a force to ‘enhance’ earnings and assets per share. Cash earns so little that treasurers can hardly get rid of their exponentially growing money piles fast enough, and buybacks give an instant sugar rush. Here we face a ‘fallacy of composition’ situation, where what is good for one unit is not good for the system as a whole. It goes well beyond buybacks, as listed stocks themselves are heading towards endangered species status.

More companies are being taken private or absorbed by larger peers than are replenishing markets via IPOs, and similar patterns are seen in Europe and the UK. According to Dealogic, US listings are down by a fifth to 1,237 and in the UK funds raised in a mere 37 listings dropped by half to £3.7bn year on year. Over the last two decades, the number of listed US companies has halved and in the last year in the US, S&P 500 buybacks and dividends together reached almost 100% of operating earnings. So, it is no surprise real economy investment and innovation are thin on the ground.

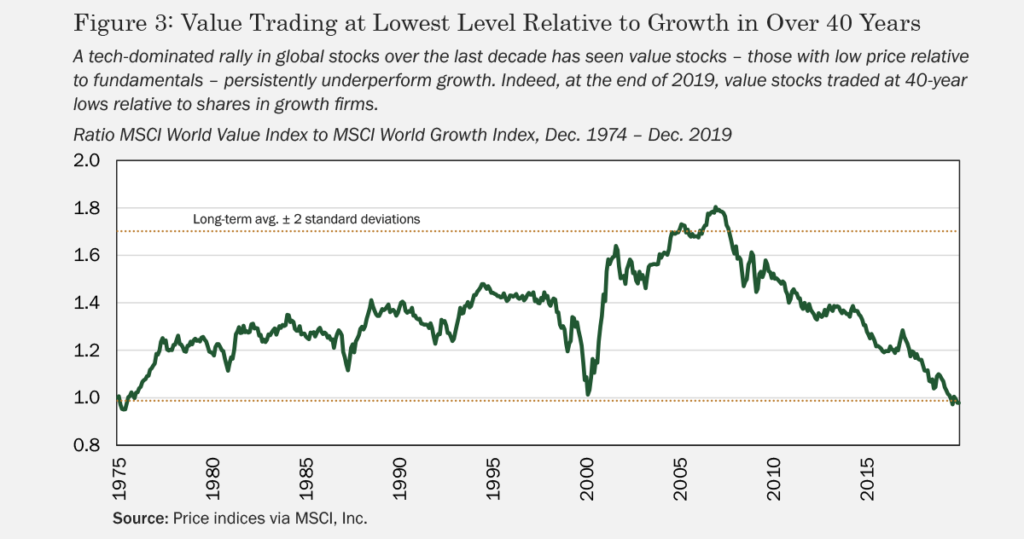

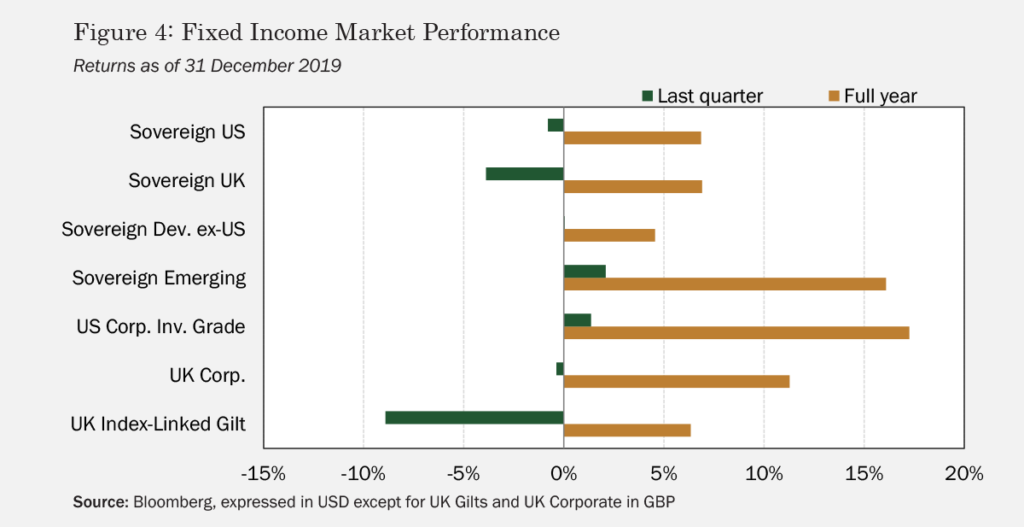

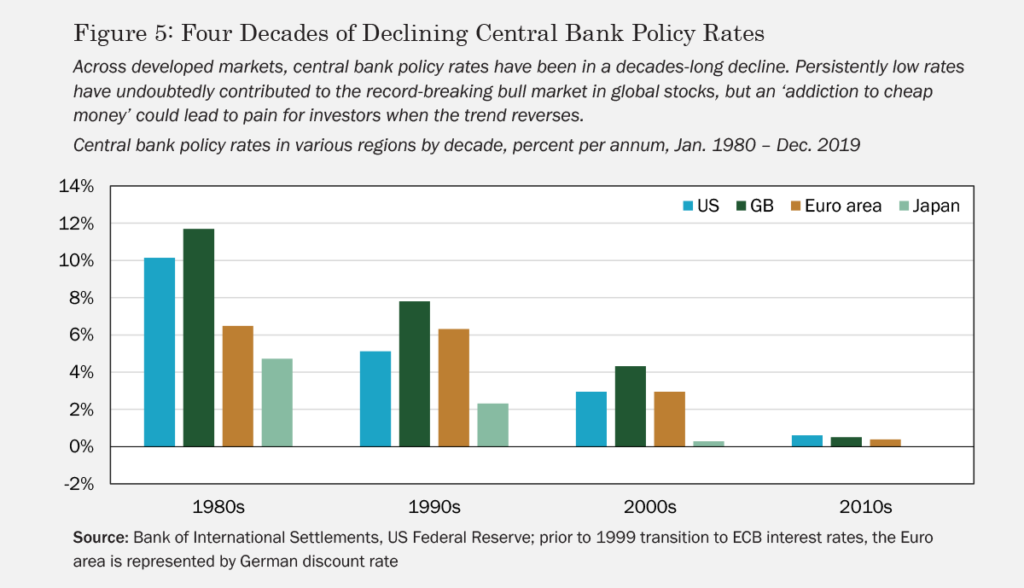

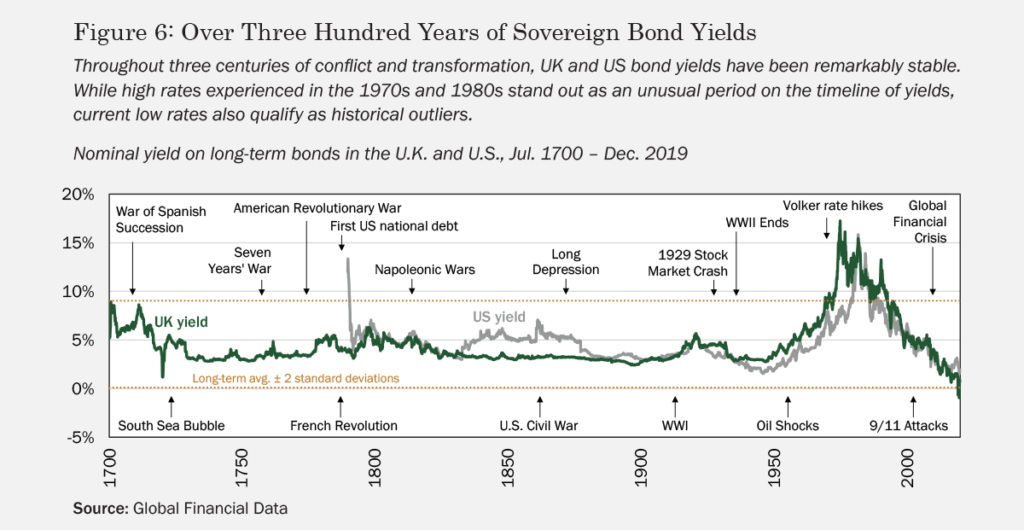

The main culprit is low interest rates. The lower the discount rate, the higher the valuation—and herein lies the secret of the market’s post Global Financial Crisis rise and the weakness of so-called valuation methods which ride lockstep with momentum. Although investors have enjoyed the ride, the more thoughtful have been concerned about this environment and what lies beyond the next loop of the roller coaster.

Of course, this misses the whole point of roller coasters, which is to keep going as fast as you can.

There are certainly plenty of things keeping momentum in place. Not least, the US Fed appears to have trouble ending QE, and needs to explain how it is going to reduce its balance sheet painlessly. In China, with debt now at 3x GDP, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission welcomed in the new year by opening its financial sector to outside investors as from January 2nd, when the Peoples’ Bank of China also cut domestic reserve requirements by 50 basis points. CBIRC is relaxing foreign shareholder limits and cancelling total asset requirements for foreign financial firms. Large banks are queuing to enter the giant market and new competition is likely to lead to consolidation of small players and improve terms for customers. But the moves are still way short of a level playing field for foreign competitors with, for instance, poor redress mechanisms against confiscation of assets.

Phase one of the US-China trade pact was signed on January 15th, de-escalating the tariff war, with the US cancelling $160 billion (out of $360 billion) of tariffs on Chinese toys and smartphones, and China committing to buy more agricultural goods and improve intellectual property rights. China Beige Book calls the deal ‘a head scratcher’ with unachievable purchase numbers and timelines, a baby trade deal and unlikely to address the uncertainties slowing investment and growth. Will it come unstuck before the November US Presidential election?

Speaking of which, we note that the S&P has only seen negative returns in four of the twenty-three election years since 1928. Professor Marshall Nickles, in his 2010 paper “Presidential Elections and Stock market Cycles”, and Yale Hirsch of the Stock Trader’s Almanac have proposed strategies to take advantage of late-cycle performance. But this would not have worked for Obama, whose early years were very profitable, and may not work for Trump, whose first year was up 30%. Despite this, we can be pretty confident Donald Trump will now be doing his utmost to keep the market flying. China is probably off the hook for now and, given the strength of its hand, maybe longer.

It is Europe that is currently attracting tariff threats as it dares tax US tech giants. It is also heading into 2020 in the teeth of a worsening manufacturing slump as it bids farewell to one of its strongest performing members. But as the last couple of weeks in the Middle East show, events change very fast and investors trading politics get whipsawed.

What is to be done? Well, the answer lies in the one part of the equation that is genuinely manageable—the investor. Only the individual can answer questions like ‘What are my objectives?’, ‘How well do I sleep at night when the market is falling?’ and so on. The adviser can help the investor arrive at sensible answers to these questions because, although we may not be able to predict market moves with precision, we do know in general how they behave over time.

Admittedly, things are not made any easier by tectonic changes in the real world. Questions like ‘Will the city I have lived in all my life be under 30 feet of water when I retire?’ do not appear in most financial advice training courses, but do seem reasonable when you read that insurers are disinvesting from fossil fuels in order to protect their shoreline property portfolios from rising sea levels. They are also removing low-cost legacy competitors from the path of their latest clean energy assets.

While dispute rages on the origins of climate change, the blame for the deeper disruption of digitalization lies entirely with humans. Along with the impact on productivity of low interest rates, the rise of vast digital empires with pan-continental or global reach has contributed to a polarization of wealth that is another source of real-world destabilization and uncertainty for investors.

Along with this destruction, these alien forces are creating huge concentrations of value and opportunities for investment gain rippling through entire sectors. The disturbances we see around us should not deter long-term investment, as new ideas feed through into markets. Deeply unsettling technologies and social conditions lay the base for the next stage of growth, a positive note for the coming decades.