“Don’t think in seas, think in oceans”

—Admiral of the Fleet, Lord J.A. Fisher

Lord Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher is considered by many as the second most important sailor in the history of the Royal Navy after Nelson. Quite some achievement in a nation that prides itself on its seafaring tradition.

Admiral Fisher’s reputation rests not on naval victories but on leadership. He could see that times-were-a-changing and if the Royal Navy didn’t abandon their traditional strengths in wooden sailing ships and embrace new technology—such as steam engines—then somebody else would, thereby ending British dominance of the seas. Fisher also realised that he needed to go further, as changing just technology was not enough by itself; the training and even the officer corps itself needed modernisation. He succeeded and secured the Royal Navy several more decades of dominance. This is an excellent, but all-too-rare example of an incumbent successfully adapting to disruptive technology and change management to achieve strategic goals.

Fisher’s attitude and vision toward change is captured in the quote above. The Admiral’s point was that often to succeed and achieve one’s long-term strategic goals, it’s necessary to have the courage to be bold and take the long-term view—to ‘see the bigger picture’ and not be overwhelmed by short-term events or noise.

Our monkey brains and fake news

Actually taking this long view is hard. There are many reasons for this, which often come down to how we, as humans, are wired. Repeated studies in human behaviour show that as a species we hate uncertainty and are more averse to loss than gain. There are strong evolutionary reasons for this with implications for our very survival. Unfortunately, while modern societies have advanced beyond recognition from our evolutionary origins, our biological software has not evolved in parallel. Meanwhile, a willingness to embrace change and accept that many things in life are random—as much as we try to fit patterns or meaning to them—is a key element to one’s success. Studies of successful entrepreneurs show that the ability to deal with ambiguity and adaptability as circumstances change is a bigger predictor of success than a fancy CV.

While in certain domains—the military and professional sports, for example—organizations have begun to embrace this perspective, for most people, battling our inner ‘monkey brains’ and taking a longer-term view is hard. Humans have other, more natural ways of dealing with danger and uncertainty. We have a tendency to act in packs, to engage in ‘groupthink’ or panic at times of greater uncertainty. Financial markets give ample opportunity for this kind of behaviour, which is the underlying driver of bubbles and busts. The recent volatility in cryptocurrencies exemplifies the dynamic, and as market liquidity deteriorates, we expect that other, more mainstream asset classes will show signs of behaviourally driven stress.

If things weren’t hard enough, whole industries have been set up to capitalise on our negative behavioural traits, perhaps none more prominent than the modern media. Quite simply, Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt (or ‘FUD’ in market parlance) sells, and that in turn drives advertising. In his book, The Science of Fear, Dan Gardner objectively demonstrates that while everyday risk has declined, perception of risk in the general population has increased. Much of the blame for this outcome falls squarely on the media and its need to drive 24-hour news cycles and sell advertising. The Swiss psychologist Rolf Dobelli, in his book Stop Reading the News, goes even further, condemning the media as actively harming our mental health and financial wealth. As Dobelli points out, reporting is largely geared toward opportunistically playing upon—and, indeed, reinforcing—our deeply ingrained biases, often produced by journalists who are rarely experts in the subject matter and often miss truly salient events or features of a story, which would have actually been useful to consumers of the news.

Oceans: What is the big picture?

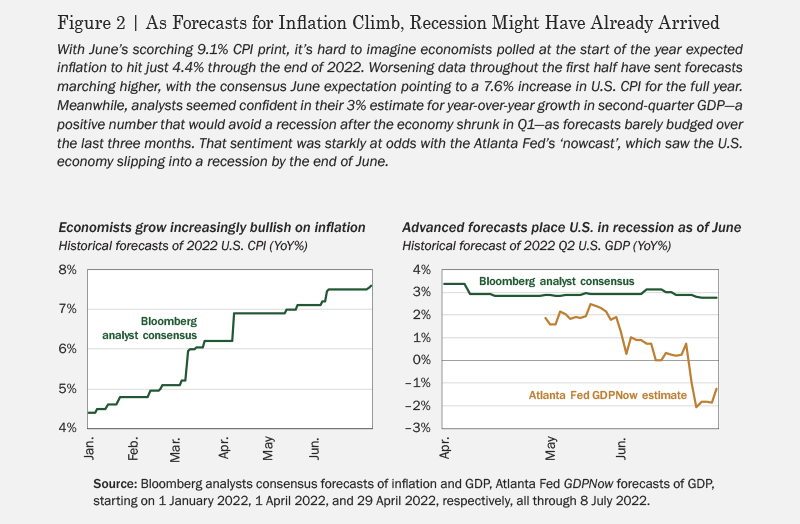

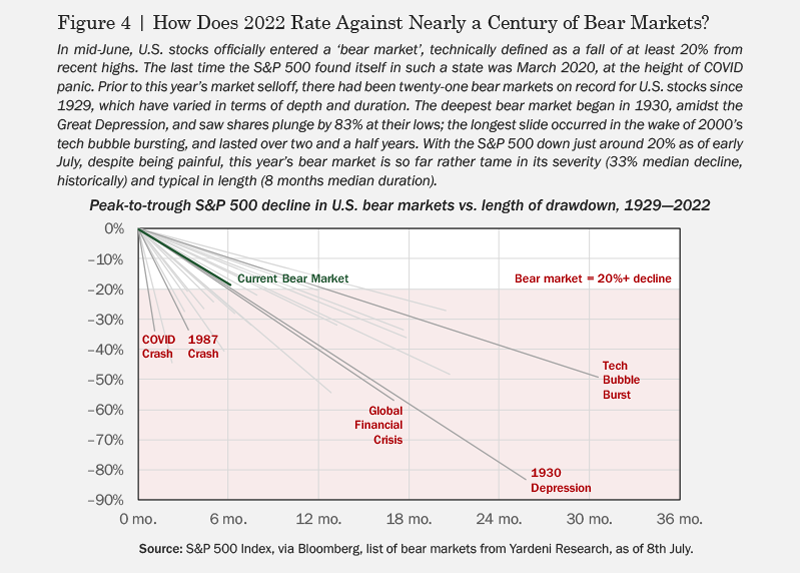

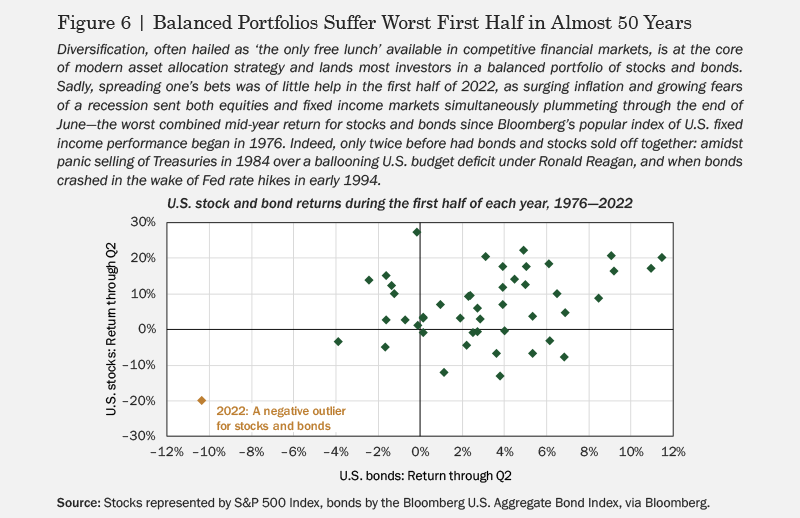

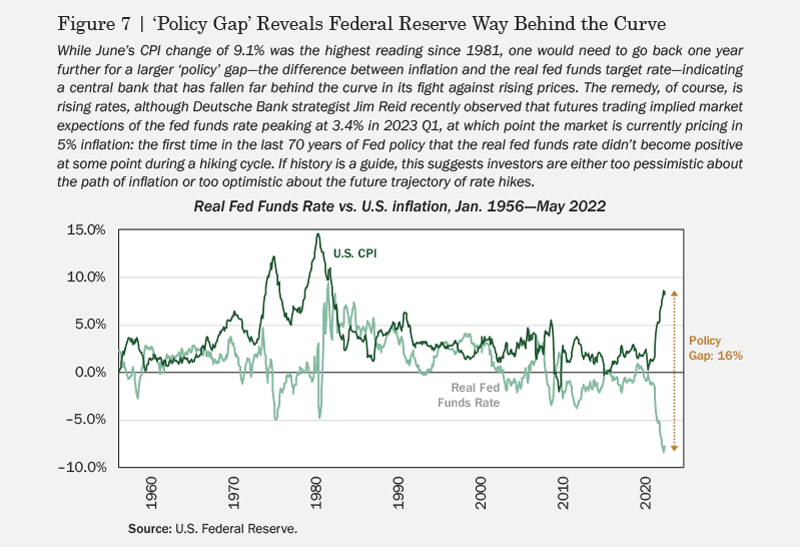

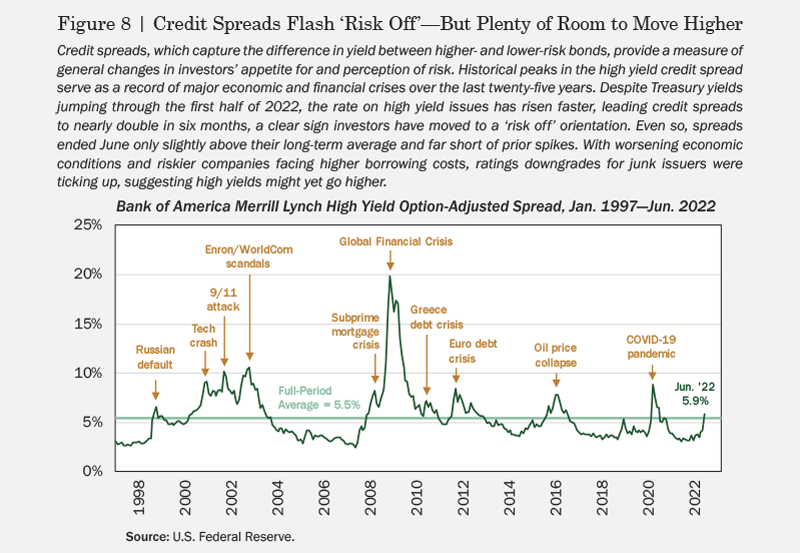

What does all of this mean for investors? Recent events are making it increasingly clear that markets and the global economy are at an inflection point: the end of a long-term trend, which is giving way to greater uncertainty and volatility that accompanies a regime shift, in the prelude to establishment of a new long-term wave. The volatility arises from many market participants facing difficulty accepting the change and simply repeating what has worked for them in the past.

Some of our competitors ‘bought the dip’ in technology stocks in January for this very reason, imagining that—as was the case in early 2020—this was the time to load up on the Teslas and Softbanks of the world. Of course, that was not the case, things have changed, and the subsequent losses have wiped out two years’ worth of gains for the client, in some cases. Whether due to laziness, lack of experience, non-existent research departments, or—worst of all—putting easy profits ahead of client outcomes, this is something we find to be almost invariably true: during long bull markets, marketing and sales departments often build portfolios, risk management and research prudence become afterthoughts (or even nuisances), and clients are the worse for it.

Just as in the run-up to 2008, seeing many of the classic characteristics of a bubble in place, we decided to stay away from highly speculative assets. In the last two years, greed, a fear of missing out, and narratives trumping valuations have dominated, as evidenced by WeWork, Klarna, Bitcoin, and Revolut. That made for a treacherous environment, and as these trades unravel, we expect to see a marked increase in negative news headlines, ‘declinism’, and predictions of disaster. The same talking heads who tried to convince you to buy U.S. tech in January will now try to convince you to sell everything or move into some new fund to cure all your woes. FUD at work.

Don’t panic!

Faced with the situation just described, what should you do? First, and most importantly: Don’t panic! You pay us to worry on your behalf and work out how to separate noise from value.

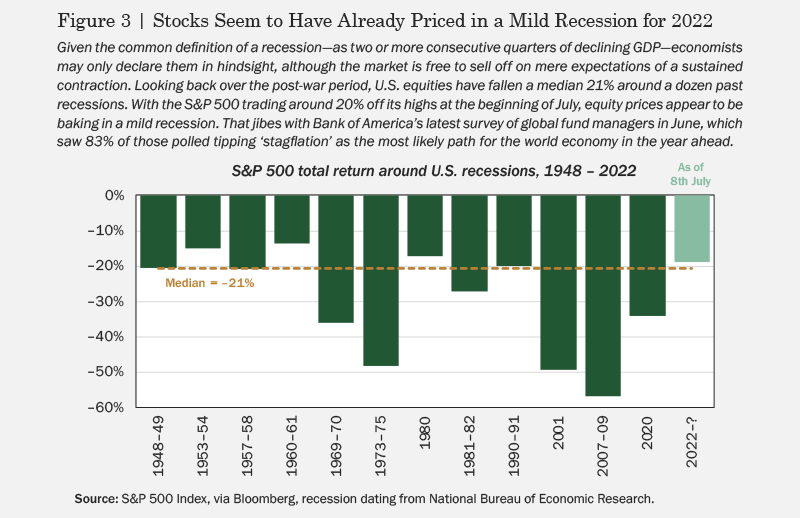

Remember what legendary U.S. investor Peter Lynch observed, “far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.” The stock market has delivered consistent returns through time despite panics, crashes, world wars, and depressions.

One of the most important factors in your long-term return when investing in any asset is the price you pay for it. We have been concerned about valuations for some time and we have constructed portfolios using evidence-based, institutional-quality processes. This approach is based on data and fundamentals, not what happens to be in fashion.

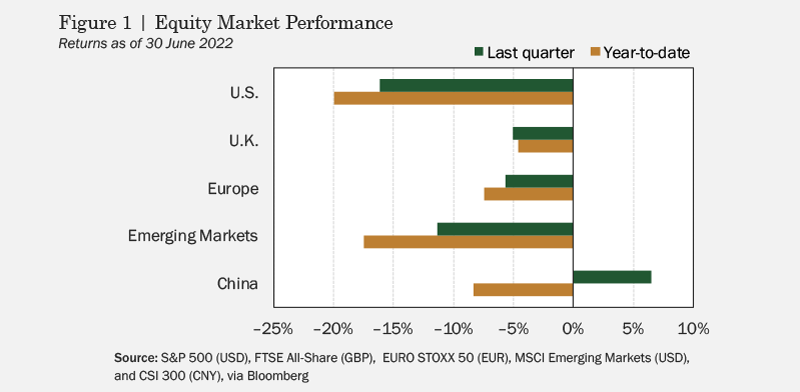

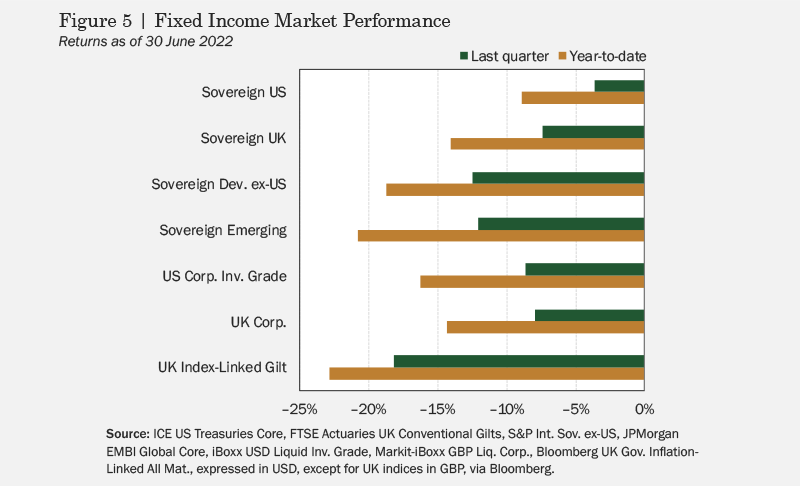

Secondly, your portfolio is diversified by asset class and geography, and tactically adjusts as markets change. Along these lines, we moved to a more defensive stance earlier in the year. Things may get grim in the U.K. and in the wider Europe in the short term. Things may look increasingly gloomy in certain economies—but a macroeconomic downturn doesn’t affect all firms equally. A number of our portfolio holdings in defensive sectors have outperformed, and we have generally benefit from continued weakness in the U.K. in our U.S. dollar position.

Thirdly, ask yourself when reading the news: How much of what you are being told is news, and how much is actually opinion? If opinion, what special insight does the journalist or media talking head have about the future, and why are they sharing it with you?

With these considerations in mind, we believe clients will have an easier time charting a safe course on the investment ocean—as well as navigating a presently stormy sea.