It is a sign of the difficulty disentangling vice from virtue that two of the shiniest examples of the clean new world, Apple and Tesla, were also two of the first victims of power cuts arising from China’s struggle to source essential coal. Humour aside, this raises critical issues: the new era of great power rivalry, inflation, and market valuation.

When Russia committed suicide with perestroika in 1991, US GDP ($6.2tn) was 12x the size of Russia’s and 7x China’s. Now it is Pax Americana that is tottering, and China is in fine fettle. China represents 16% of World GDP, the US 24%. This makes the asset allocation decision with respect to China easier. Mr. Xi is unlikely to throw away the gains of the last few decades on hot wars with Taiwan and other neighbours, at least not until he has developed the technology and production capacity to replace western semiconductor manufacture. The US has a strong hand. It controls the international payments system, has a technology, military, food and energy resource lead and a huge import market. Together with allies, it commands 60% of World GDP. China has more up its sleeve. It has cornered the clean energy supply chain and is on the verge of creating a digital currency that will block US sanctions via Swift. Xi has centralised vertical power for a reason. He is remoulding Big Tech, boosting Party legitimacy by changing the way wealth is generated. The aim is to transform factor productivity, allowing smaller enterprises to prosper using the nation’s deep technology stack. As China lets the steam out of its property sector, it is clear there is a shift to a new model led by hard tech. In many areas, the West is years behind and the US is right to fear loss of hegemony. An added attraction is that China is not reliant on the Magic Money Tree. Xi’s ‘Common Prosperity’ strategy shows he takes the interests of China’s equivalent of the ‘median voter’ as a serious constraint.

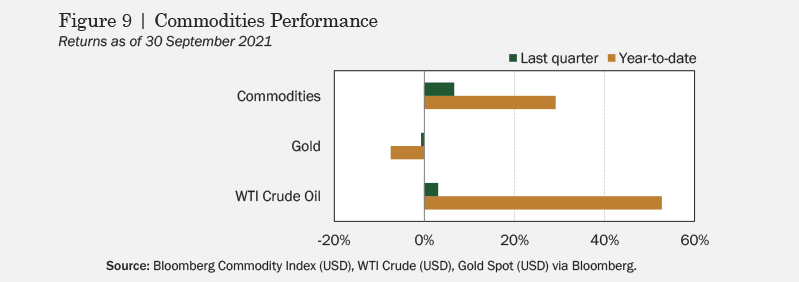

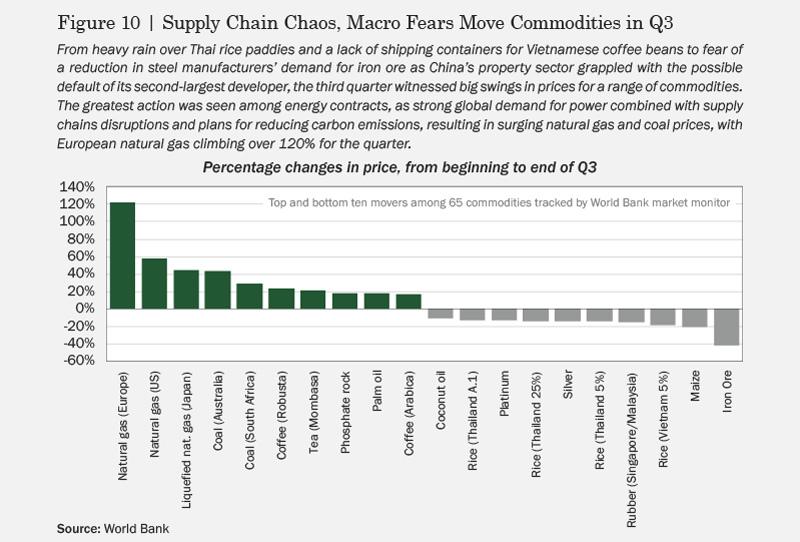

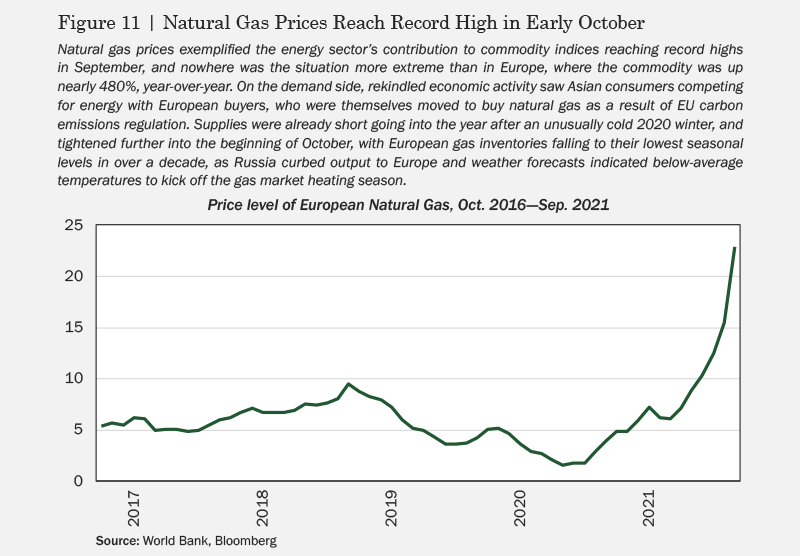

Worldwide, median voters have not been well served by lockdown as global supply chain issues force energy, food, and many other goods’ prices higher. While headline CPI rates are still in the 3-5% range, energy inflation is near 20% due to resource shortages everywhere you look. Even in the US there are winter blackout warnings. China’s coal-fired power plants are caught between price regulation and soaring coal costs, as drought hits hydro power. Poor energy strategy decisions over many years in Germany and Britain are coming home to roost. As Buffet says, ‘You see who is swimming naked when the tide goes out.’

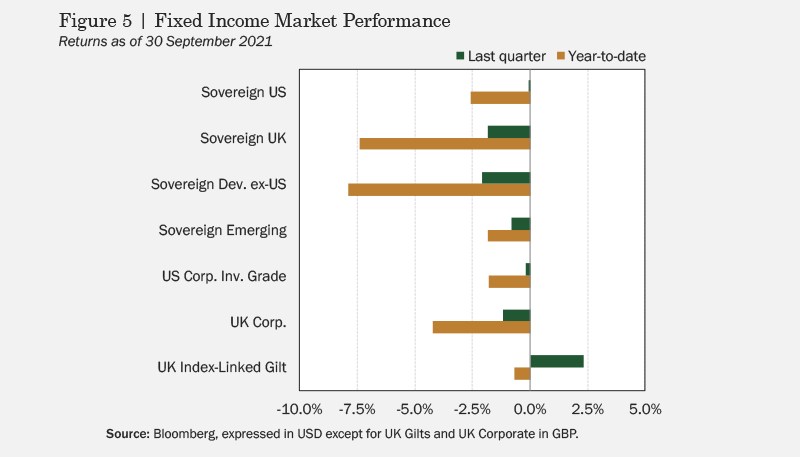

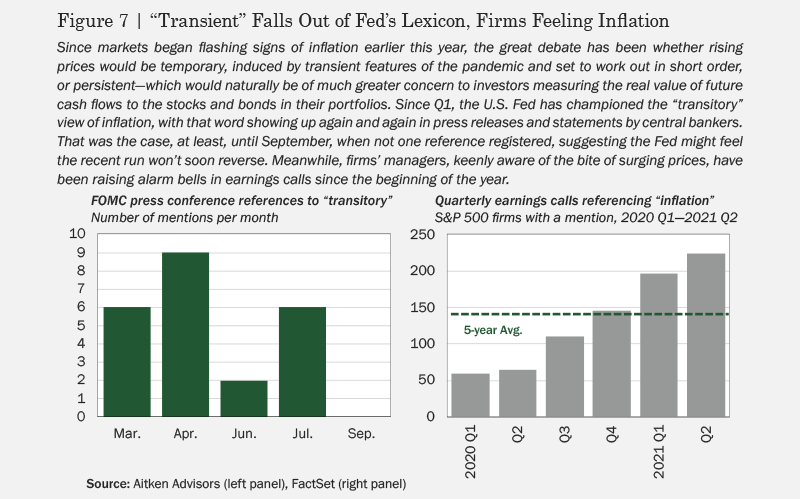

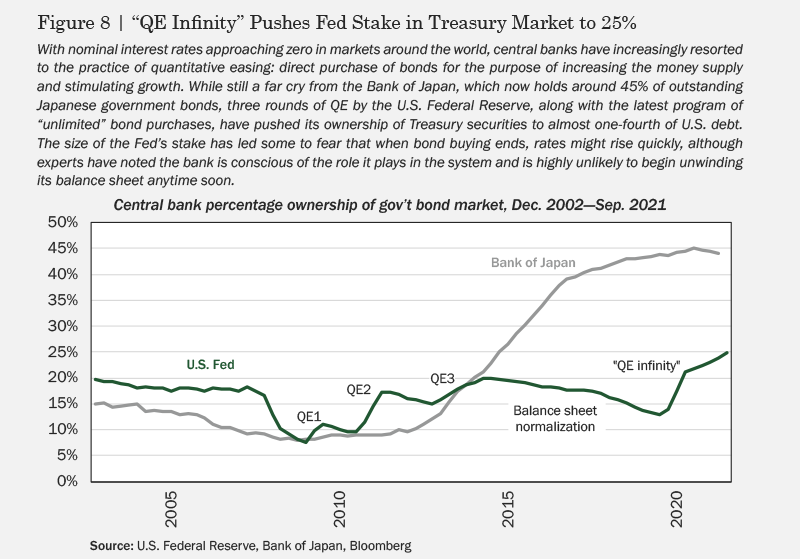

The bottleneck crunch should work itself out, despite central bankers stretching the definition of ‘transitory’. Every sector is different, some products spiking in both directions, with others on a slower burn. For example, UK house prices have risen 25% but rents have barely moved, a situation in danger of seeping into CPI given wage pressures. It is in lingering second-order effects that risks lie. The UK labour market has Brexit distortions and public sector political pressure, while the US has an 8 million job output gap. The IMF has called for central banks to get ahead of the curve if prices rise too fast or economies overheat, even without full employment.

Between bond yields peaking in 1982 and the 2008 GFC we lived in a deflationary regime. This changed with the GFC. Aversion to the deflationary impact of globalisation ushered in Brexit and Trump. China will not emerge again, and India has missed the boat. Baby boomers are leaving the workforce, female labour participation is flatlining and digital technology is diffusing at a sedate pace. Lockdown just pumped a triple monetary, supply, and demand shock into a system no longer proof against inflation.

How bad is inflation for investors? The record seems to show that inflation rates above 4% or 5% impact equity returns. This is attributed to companies not being able to fully pass on costs to customers, hurting profits and valuation multiples. But it is also likely the harm is caused by interest rates hikes to quell inflation hitting growth and discount rates, and scope for such rises is limited.

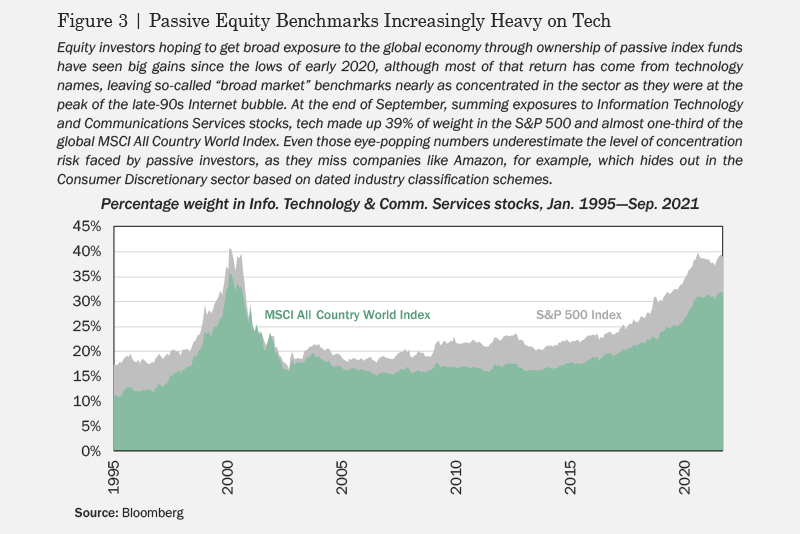

Which brings us to equity valuation. Where are we as we near the end of the monetary expansion that has fuelled the rally? Most ratios are bad guides to market direction. One or two measures, like q, (the ratio of the S&P’s market cap to the replacement value of net assets) and CAPE (the Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio) have a better record. Today, the Fed q stands at around 2x, which is high, while CAPE suggests 45% overvaluation. But this does not allow for the monetary background. Taking the broad US equity market against liquidity, the Willshire 5000 Index divided by M2 money supply, the measure is high, but not extreme. In the late 1990s, the ratio peaked around 3x, while today it sits at just over 2x. With inflation at 5%, interest rates at 0%, it is easy to see this as reasonable.

Looking at markets in more detail there are a surprising number of realistic value opportunities. With rising energy and material prices many miners look cheap, banks are a yield pick-up play and there are property REITs with low debt and index-linked rental income. Even the mature tech giants tick the right boxes: market dominance, cash rich, high margin, and pouring money into innovation. Google may spend more on quantum computing R&D than China. China itself, the Saudi of data, is bristling with well-capitalised advanced technology stocks. As to the seeds for the next generation of giants, one of the lessons of our oil and gas price spikes is that clean energy investment needs to intensify. Space, AI, energy storage, quantum computing are other areas sucking in speculative capital at scale.