Market Overview

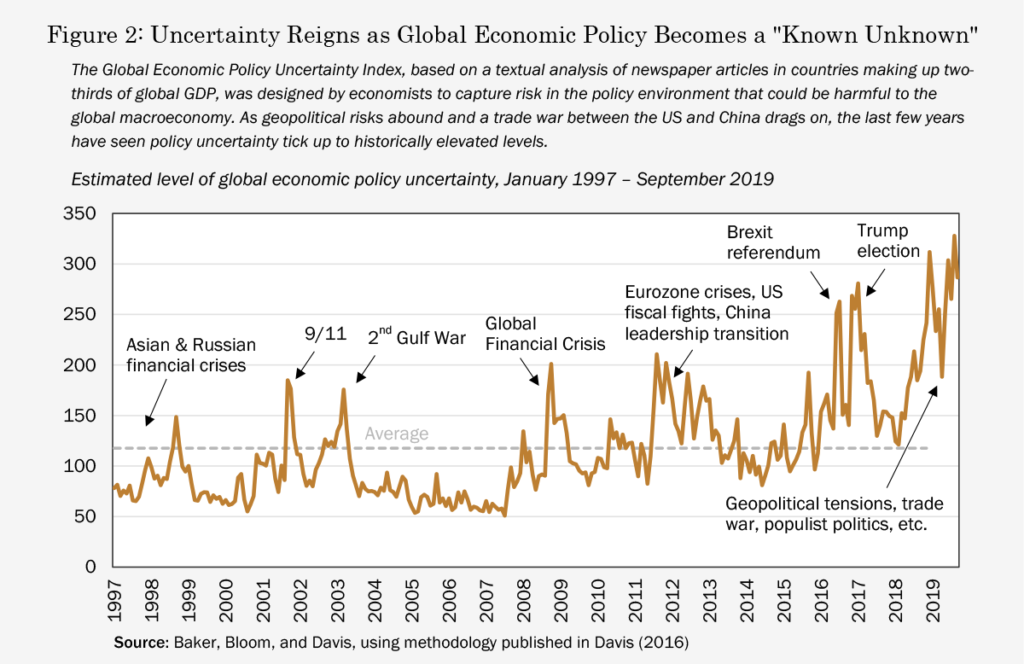

While currency, equity and bond markets yo-yo at the mercy of Trade War headlines it is worth recalling the story that in the 1420s China sent a massive fleet all the way to Europe helping to trigger the Renaissance. It did not end well. All evidence of the voyage was destroyed by envious Beijing bureaucrats. Today, adventurous Chinese businesses are fully supported by their state but now it is their strategic rival, the USA, that wishes them ill. The Trade War has deeper roots than trade, and as China’s military and economic prowess increase, so do US strategists’ concerns at their shrinking lead in technologies and resources. Attempts by Mr. Trump to partially or completely excise China from the US dominated financial system add an extra frisson to nervous global markets.

With China’s equity markets the same size as Europe’s, it is a little late for Mr. Trump to stuff this genie back in its bottle unless he wants a real fight. Meanwhile WTO data show trade is already suffering and based on PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index) numbers, the US does not look to be winning the conflict. China’s latest Caixin Manufacturing PMI surprised positively at 51.4, with new orders up at their fastest pace since March 2018, despite declining exports. China has proved itself adept at pulling the right macro levers. Compare this with the US’ trade war ‘own goal’ PMI, an abysmal 47.8 and, underlining an even greater dependence on trade, Germany’s reading of 41.7.

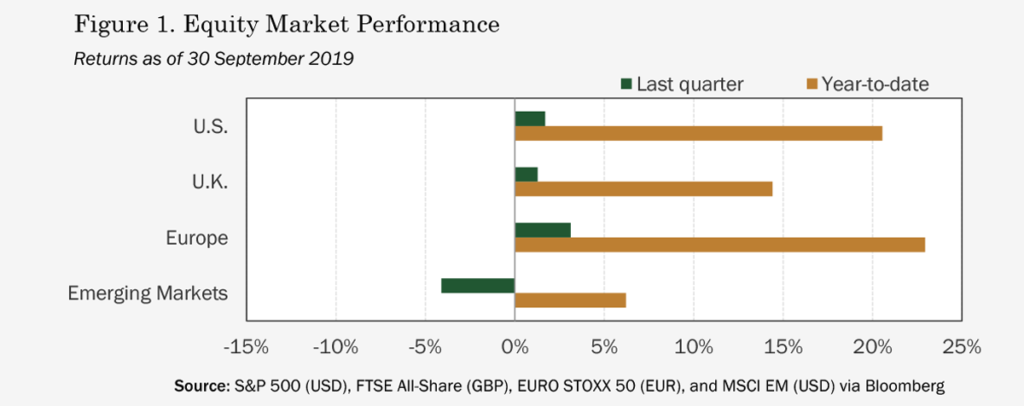

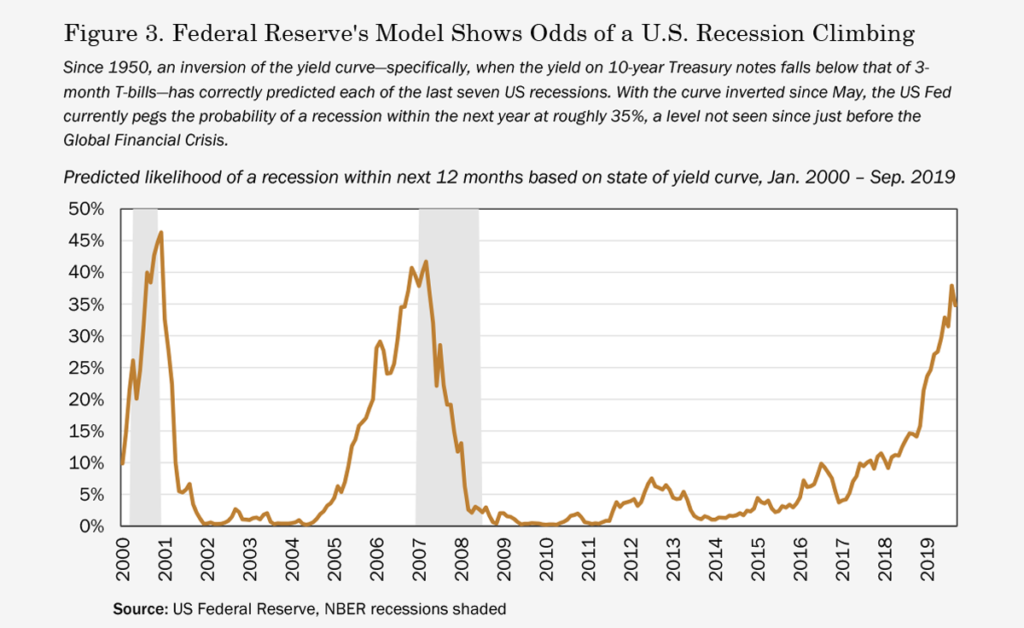

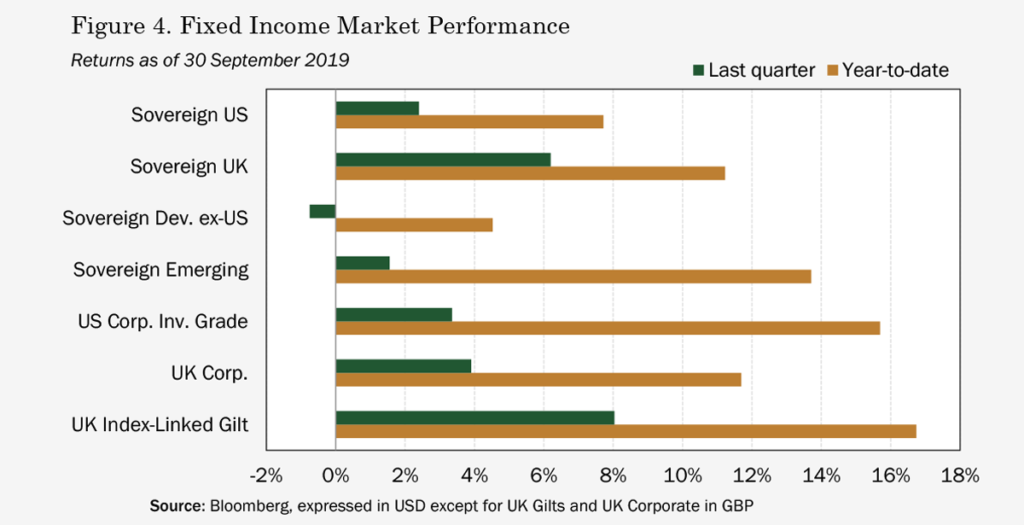

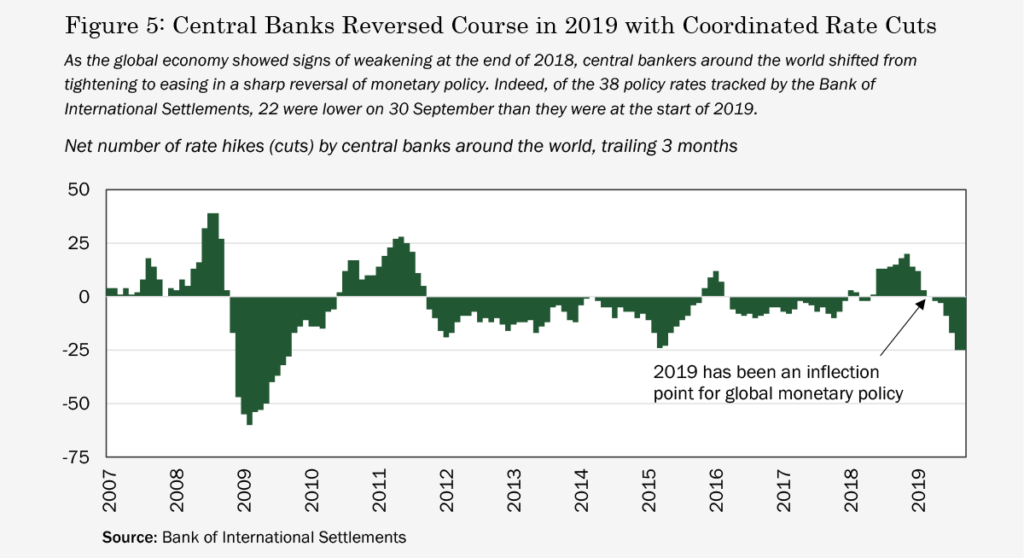

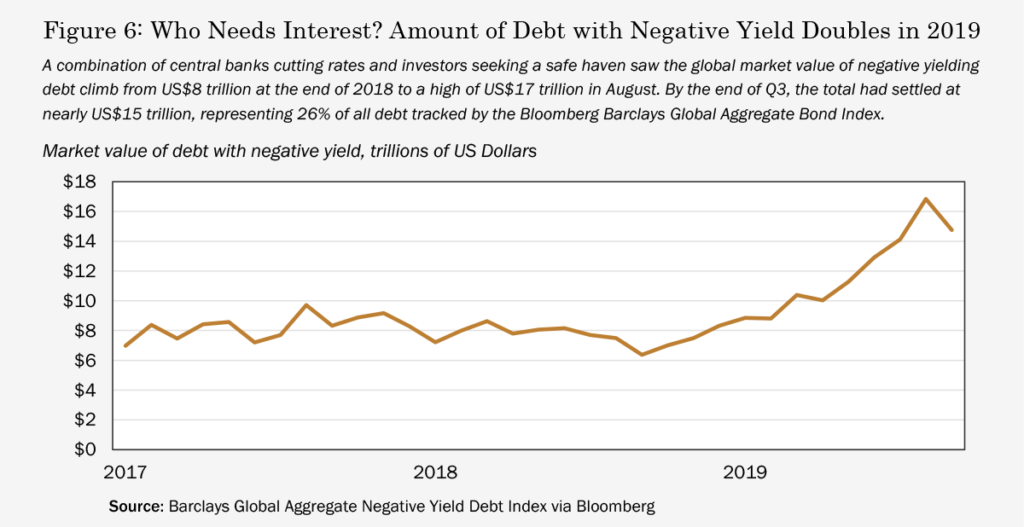

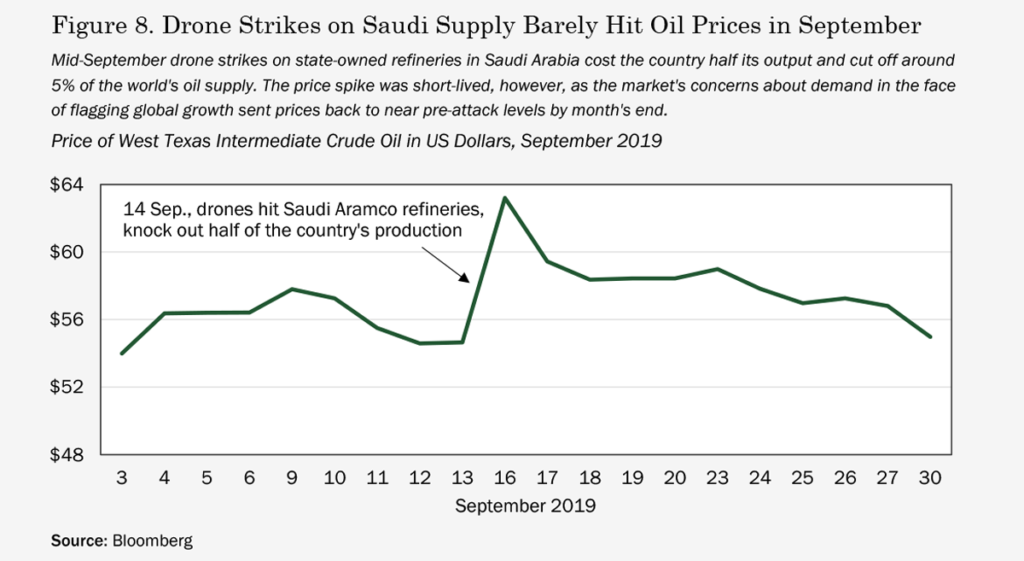

The Brexit drama too is laden with historic baggage and threatens more disruption to trade systems. It joins the Middle East, Hong Kong and Argentina as crisis catalysts. With a background against which several apocalyptic scenarios can be painted, equity markets, especially those in the US, have trickled along at current levels for the last two years. Strong US employment figures and unusually low wage and inflation pressure give the Fed breathing room for a couple of 25 basis point rate cuts before December to shore up confidence. But extended low rates are part of the problem, and Draghi’s final shots from the ECB have encountered strong resistance from member states, exhausted by years of intervention and weak growth. The IMF’s latest deeply gloomy report points to how low rates force investors and companies to seek high-risk returns. It also argues trade wars will cost US$700 billion per year as confidence plummets and that US$19 trillion of corporate debt is at risk of default.

The S&P 500 Index’s forward P/E is 19x, against a range of 35x–10x since 2000. The bottom of that range marked 2009. Could markets descend to such levels again in the near future, extra painful if underlying earnings fall in a recession? It is possible to argue investors are overly nervous, anchoring on memories of the Global Financial Crisis. But debt concerns are visible in several directions. Recent government bond auctions in the US, Germany and Japan have struggled. As the annual US Federal deficit hits US$984 billion in 2019, equivalent to 4% of GDP, the consumer also looks exposed. Automotive manufacturers and lenders from Capital One to Ping An have been loading buyers with unaffordable debt. A third of US buyers roll debt from old cars into new ones as the average loan stretches to 69 months, a record.

Such data make investors nervous. But the rationale for holding equities is long run growth and this still applies, though the productivity engine runs quietly and is hard to detect in short-term returns. For example, our well-heeled friends in Extinction Rebellion inadvertently remind us of ample investment opportunities via green environment and energy projects: the Bill Gates backed Global Commission on Adaptation’s conveniently timed report, ‘Adapt Now’, highlights five areas where US$1.8 trillion invested could generate US$7.1 trillion net benefits between 2020 and 2030, with plenty more where that came from. While these returns are not purely financial, the scale of the emerging green investment universe is massive. Similarly, disruptive demographic changes like ageing populations and mass migration conceal huge shifts that have been driving growth for many years. China alone is seeing so much value in its rapidly growing urban middle class that its tech giants are focusing almost entirely on their domestic market. Expansive development is taking place elsewhere in Asia as well.

Many other forces are quietly humming under the hood, steadily delivering efficiencies and new capabilities. Developments in quantum computing, for instance, promise massive increases in computational power at a fraction of current energy consumption. And the National Academy of Sciences reckons a mere US$200 million per year investment could lead to commercially viable fusion reactors – the ultimate clean energy – before 2050. There are many such stories, hard to quantify but cumulatively powerful. It is reasonable to look at the shape of the financial system with concern, but investors (and climate change activists) can take comfort from long-run changes in population and technology that promise more wealth creation and environmental benefits to come, lifting millions more into prosperity. The long-term equity bet remains intact.