Before talking about the UK budget and the subsequent moves in GBP and Gilts, everything needs to be set in a wider perspective.

- The post-cold-war system is failing, it’s been failing for a while, and it may not be possible to resurrect it. Most market commentators haven’t grasped this. Everything from Brexit, Trump, the rise of Le Pen or the recent Italian election results needs to be seen in this context. The Covid crisis just accelerated events.

- The US dollar is the centrepiece of this system. Many countries have come to rely on cheap funding to make their economies work. Now the US is finally tightening up monetary conditions it is making the dollar scarce internationally. This is effectively creating something like a global funding squeeze, and it is likely to continue.

- The UK mini-budget on Friday needs to be seen in this broader perspective. In many ways, it represents a positive change compared to the policies of the past 30 years. The economic performance of the UK has been poor since the Global Financial Crisis. This has been caused by a variety of factors and administrations.

- The UK’s reaction to Covid has put the public finances and services under pressure due to poor timing, implementation and the UK’s market structure. We have inflationary pressures after far too much “easy money” and the Bank of England has been slow to react. The post-2008 market regulation has pushed a lot of risk into markets, which will increase volatility and the low yields have forced lots of investors to take risky bets.

- Combined with this, we have a lot of long-term investors like pension funds and insurance companies that have been forced into complicated investments due to low yields. They rely on liquidity and moderate volatility to manage these. The unexpected nature of the budget may have unintentionally caused these investments to backfire. This will push yields higher and cause a marked problem for the government’s plans.

- Finally, international investors are increasingly benchmarking investments to the increasingly attractive returns and security offered by the US dollar the world’s reserve currency. If UK base rates are not going to rise materially to offset this, then the currency and bond yields have to cheapen to compensate.

“If you don’t read the newspaper you are uninformed, if you do read the newspaper you are misinformed.”

— Mark Twain

In our last note, we highlighted that headlines were likely to get worse and the media would capitalise on it. With the mini-budget last week we saw an example of this.

Despite the prevailing negative coverage from the media, I don’t think there are a lot of good alternative choices either. The UK has been in an effective slump since the Global Financial Crisis and on many metrics, it is starting to look like one of the poorer US states. This is not a result of Brexit, as many have claimed, as these issues started to appear long before the referendum and indeed, the case could be made the Eurocrisis contributed to them.

The country’s tax burdens are also at post-war highs and there is very little evidence you can “tax your way to prosperity” as Churchill once said. So, the budget could be crudely described as a higher risk/high return attempt to grow the economy faster than its debts. Even the objectives are relatively modest with the aim to get the economy back to its longer-term trend growth rate rather than turbocharge it.

Despite the noise and negativity from the media and dismal scientists, I have a lot of sympathy for what the Truss administration is trying to do. That said, it’s not without its risks. It’s much more aggressive than I, and evidently, the wider market, expected. There are some key points worth looking at.

First, it looks disjointed with the BoE only raising rates by 0.5% the previous day and announcing the start of quantitative tightening it’s a lot of additional UK bonds for the market to suddenly be expected to finance. The government appears to have focused on the UK’s absolute rate of debt vs its peers rather than the fact markets are made on the margin and the additional unexpected supply needs to be priced to clear. Using a standard approach to economics, this would suggest the UK base rates need to be much higher, something the country can ill afford due to the nature of the mortgage market. If the BoE is hesitant to do this, then the currency and bond yields have to cheapen to do the job.

There is a risk here that for a variety of technical reasons the unexpected size of the government’s demands triggers higher volatility in the bond market. There are several large UK institutional investors that have made complicated investments due to low yields and – ironically – Gordon Brown’s long-forgotten wrecking of a section of the UK pension industry. The financial engineering involved makes several heroic assumptions, especially around market liquidity and how the products they have used will behave in an environment, they have never seen – an inflationary bust and an aggressive Federal Reserve. Complexity is the nemesis of risk management which is why we have avoided structured products in our portfolios.

Second, it’s only half the required measures as despite there being a broad policy document there is still a lack of detail on supply-side reform. To generate higher growth rates reforms will be required, that have yet to be fleshed out.

Third, the UK appears to have a tight labour market and the country is already running above targeted inflation. Many of these measures look inflationary. The last time the UK attempted something similar was in the early 1970s under the Heath administration, as known as the “Barber boom.” It ended up as an inflationary mess with the IMF support package.

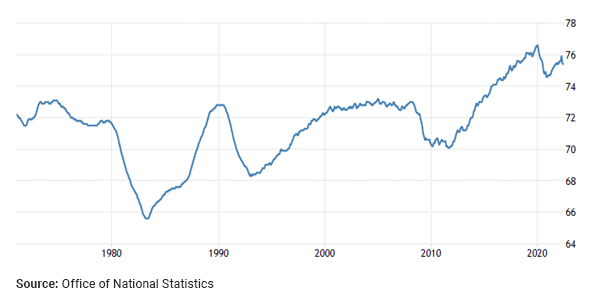

Chart: UK Employment Rate (% of 16–64 year olds in work)

However, there are important differences this time around. The UK in the 1970s was also near full employment but with a highly unionised and unreformed economy. Now the UK labour market is a lot more flexible. Also, the employment rate disguises the fact that there are a lot of low-wage, low-productivity jobs. Male employment ratios are also much lower and have been dipping in the 50+ age range since Covid.

In the 1970s there were still foreign exchange controls, which meant the currency couldn’t take the strain like it’s doing now. Despite many witless comments, the UK isn’t an emerging market economy for a whole variety of reasons but most importantly, as the UK government has relatively few foreign currency debts, this makes a full-blown emerging market crisis harder. But the cheapening of bond yields does push up government debt payments which is an issue and the weak currency runs the risk of importing inflation, which makes the BoE’s job even harder. A lot of this can be traced back to the BoE’s behaviour during the Covid crisis1.

So, I would hope and expect for some reforms and spending restraint to be announced in November. This might prove politically difficult to put it mildly. Whether the electorate or even the Conservative party is willing to follow through with this remains debatable. As that great admirer of the Conservative Party, Jean-Claude Juncker, once put it “we all know what to do but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we have done it.”

Regarding the GBP

The USD is on a massive rally due to the Fed determination to push up rates to push out inflation. Even after this episode the UK hasn’t got the worse performing currency this year. The belongs to the Japanese Yen (see below), this is even more problematic for the Japanese financial system due to their massive borrowings in USD. A point I highlighted in this article.

Chart: The Dollar Index (DXY) continues to rally against the major currencies

Table: Who had the Brazilian Real on their best performing major currency YTD? Anyone?

Since the UK cannot push up base rates to match the US, the currency and bonds cheapen (offer higher interest) to compensate investors. I think this will carry on – with some rallies – into next year.

The sharp movements are because the post financial crisis reforms have pushed risk out of banks and into markets. So, I expect volatility to become more extreme. Steeper yield curves will push up the government’s interest payments and the BoE may have to step in again to stabilise the bond market and provide liquidity.

However, this is all noise. The big picture is the Fed is determined to get US inflation down, this means significant headwinds to speculative asset prices, rising unemployment and possibly a hard landing. Alternatively, given the credit-driven and highly leveraged nature of the US economy, a much quicker slow-down could be possible. The key thing is the US is doing what best suits itself and that is a big change from the past 40 years.

Secondly, Europe is heading into a deep recession with even weaker fundamentals than the UK and far less flexibility. The Eurozone looks even worse than the UK, which is why the two currencies remain within their normal ranges. Rather like 2008/2009 when the market focused on the UK and rather overlooked the growing problems in the Eurozone.

Chart: It’s not a UK-specific thing; the USD rally is pushing many countries before it. EUR/GBP remains within the long-term range.

Never let a good crisis go to waste

The UK is having its time in the doghouse, but we do not expect it to be alone nor to be the worst dog. As those of you who came to our recent investor evening know, we have been positioned defensively for a while with a strong bias towards US dollar assets.

Whilst the first stage of the UK’s change of strategy may have been fumbled the country’s growth plans are still a work in progress. The UK remains one of the world’s largest, most technologically advanced and dynamic economies.

Finally, as Napoleon is alleged to have said, “I would rather have a lucky general rather than one that is good.” It may well prove that as time progresses, the UK looks relatively more attractive, and some UK assets are now getting very cheap indeed. Whatever happens, we hope to capitalise on this and remain patient as events unfold.

Endnotes

1The BlondeMoney podcast from Jan 2021 with former deputy BoE governor Sir Paul Tucker contains an excellent prediction of the BoE’s likely future issues due to its Covid response.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Henderson Rowe is a registered trading name of Henderson Rowe Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under Firm Reference Number 401809.

The information contained in this article is the opinion of Henderson Rowe and does not represent investment advice. The value of investment may go up and down and investors may not get back what they invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.