Comparing one’s annual investment return from your own personal trading account against the portfolio run by a professional is a tempting exercise. Even with great near-term performance, should investors expect to be ahead of the professionals after ten years? Dom Wright, Head of Client Services, looks into the historical research for answers.

Let us imagine you are playing a round of golf against Hideki Matsuyama, recent winner of the 2021 Masters. On the first hole, he shoots into the water, takes a drop and finishes two over. You, on the other hand, make a solid par and are already two shots ahead of him. You walk off the first green with a spring in your step and float towards the second tee. However, he’s the one with the Green Jacket, so would you realistically expect to still be ahead after 18 holes?

Similarly, imagine you’re comparing the annual investment return from your own personal trading account against the portfolio run by your Investment Manager. Over the year, your single name stock pick, Tesla, gains more than 700%, whilst your Investment Manager’s strategy lags behind, despite being put together by a team of 14 PhD researchers with over three hundred years of investment experience. Would you realistically still expect to be ahead of your manager after ten years?

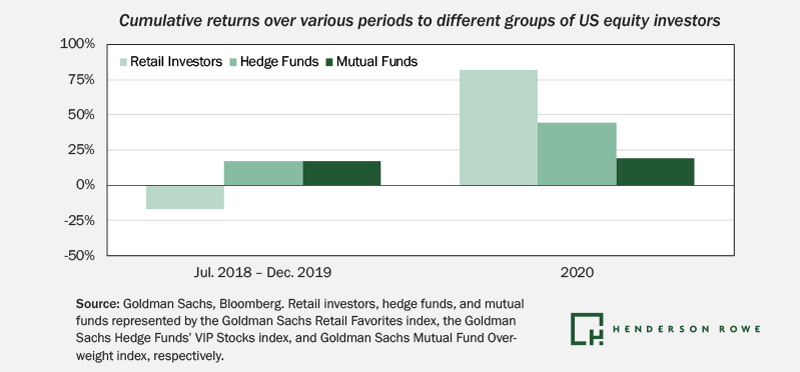

2020 was an extraordinary year for all sorts of reasons. According to data from Goldman Sachs, amateur stock traders gained 80% on average in 2020, more than four times the gain they might have seen by investing in a mutual fund. This contrasts with a -17% loss suffered by retail investor portfolios over the prior 18 months, versus a 17% gain for institutional investors.

Proving their worth is a particular challenge faced by Investment Managers and it is not an investment problem: it is a statistical one. At any given time, approximately one third of Investment Management clients will be more bearish than their manager and wanting to “cash in”; one third will be more bullish and will want to pounce aggressively and one third will be aligned with their manager.

Therefore, one third will outperform their manager if the market rallies. One third will, unjustifiably, think their manager is incompetent if the market falls. And one third will think we are all idiots anyway. Plenty of people think that they can time the market and that just putting all their money in one single stock has a chance of beating a well-thought-out strategy. Sometimes it does, but research shows that no one can consistently time the market: it is mainly luck.

We know that individual investors tend to have more concentrated stock picks, with bias to their home country, to household names and to “in vogue” stock picks. Clearly these tendencies have paid off in 2020, but when we say that short run performance isn’t relevant, it’s not because we want to shirk our responsibility.

“No matter how great the talent or efforts, some things just take time. You can’t produce a baby in one month by getting nine women pregnant.” — Warren Buffett

Research reported by Jason Zweig of Wall Street Journal, found that on average, investment institutions achieved a return of 7.5% per annum over the last 30 years, whereas retail investors with advisors made 4.5-5% and individual retail investors without advisors made an annual return of -2%.

But returns alone do not account for risk. The trading portfolios of retail investors tend to have much higher volatility risk, because of the concentration, which is usually closer to 30% while institutional portfolios are closer to 9%.

In the short run, if both an institutional investor and a retail investor are lucky and achieve a positive one standard deviation event, the institution will achieve 7.5% + 9% = 16.5% return but an individual will achieve -2% + 30% = 28%. When both parties are “lucky”, individuals think institutions are stupid and don’t actually know how to make money.

Conversely, when individuals have a negative one standard deviation event, the -2% -30% = -32% return is rationalized by the individual as “fun gambling” on a small sum. Humans suffer from hindsight bias and shift their goal to confirm their beliefs such that they reason, “in exactly one month I’ve done better than the professionals.”

Ultimately, the performance of institutional products is designed to be more predictable, and as a result, we look at returns in the context of what we would expect. What an Investment Manager should be trying to deliver is an “institutional product” that minimizes the impact of noise and luck; they should be implementing a process that is rigorous, systematic and explainable. So, even if you want to gamble a bit, you still have a sound core to your portfolio. Our suggestions to achieve this are:

- Always focus on process more than performance;

- Avoid expensive, opaque and illiquid products;

- Invest into transparent, liquid, steadier investments (therefore less sexy);

- Make sure you understand the strategy you are invested into. If it can’t be explained to a six-year-old it is probably a lot of “hot air”.

Hindsight is always 20:20 and things are never clear at the time you invest. So, good quality institutions should rely on their process and methodology to guide them during volatile times. They cannot outperform your personal picks where you have remarkable knowledge or unique insight, or where you are able to take large specific risk in concentrated sectors and companies.

That’s why even when we are confronted by these “short-term losses vs a client’s short-term wins” scenarios, we stick to our guns on process.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

Henderson Rowe is a registered trading name of Henderson Rowe Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under Firm Reference Number 401809.

The information contained in this article is the opinion of Henderson Rowe and does not represent investment advice. The value of investment may go up and down and investors may not get back what they invested. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.